One of the most rewarding aspects of teaching is the thoughtful questions asked by students. Indeed, these queries have often inspired these blog articles.

Two related areas of concern pop up fairly regularly in both teaching and reader inquiry: could there be more Tones than the classic 12 “keys” and are there “spaces between the tones” that these tonal divisions do not consider?

The first question was addressed in a previous article ‘Are There More Than 12-tones Available in a Personal Colour System (July 2011)?‘. The short answer is yes, of course the 12-tones could be subdivided further, but the natural realm of colour is vast, and while we could in theory create 100’s of different tonal groups within a personal colour system, our ability to distinguish meaningful difference is limited by our visual capability as human beings. If we are unable to see the difference between hues from one tone to the next, then the exercise would serve no purpose. (For the sake of argument, if we were to create more divisions then the next natural order of division would take us from 12 to 24 tones. This would reduce the number of distinct hues available to each grouping, and make many more indistinguishable from each other, or more confusion to little purpose.) Experience suggests, further, that individual clients often have their own personal favourite neutrals and accents within their palette, in effect creating their own “microclimate” within their tone.

The second question, like the first, is often prompted by reading about systems which propose something other than twelve groups of personal colour. Readers ask it in various ways: “Could there be tones that combine spring and autumn – they’re both warm, so why can’t or don’t they “flow” together?” “Is there a tone space in between existing tones, say between bright spring and dark autumn or true winter and true summer, which isn’t accounted for in 12-Tone theory? Is it possible that an area of colour space has been overlooked?” “What about Deep Bright Winter or Soft Summer Light? Could there be such a thing?”

To give these questions their due, we must once again go back to first principles.

The finest and most accurate rendition of a natural colour harmony system (Sci\ART) was defined and refined over many years by the late artist and Munsell Master Colourist Kathryn Kalisz, and each of the 12-tones had a consistent and harmonious character, based on its overall relationship to the three axes of colour: value (lightness or darkness), chroma (saturation or intensity/brightness of colour) and hue (the base colour itself, whether a red, orange, blue-green, or whatever.) Colour space could be arbitrarily divided in any number of myriad ways and there is nothing to stop anyone putting *any* combination of colours together for a particular effect (see previous articles “Is Disharmony Ever Desirable”and “Change Takes Time – Tonal Contentment vs Tonal Restlessness” part IV and V for a fuller discussion Of this), but a naturalistic harmony and an avoidance of artifice based on close attention to these organic characteristics of colour is the distinguishing feature and aim of the SciART system.

The SciART System (as originaly devised and when it was overseen by Kalisz) was based on the way colour behaves in nature, and organises colour in ways that respect these natural principles. A colour can be light, medium, dark, medium light, or medium dark, but it cannot be more than one of these: that is, it cannot be in two places on the value scale at once. Similarly, it can be high or low chroma, or a particular hue, but again, it will occupy a specific place on each axis in the grand scheme of colour and will fit at only one point of colour space. Finally, colour moves from warm to cool to warm to cool as we go across the spectrum and around the colour wheel, and the SciART progression of tones always respects this physical rule. We will take these points in turn as we consider the question of “tones between the tones”.

Changing value and chroma alters a colour in a predictable and consistent way, and the results of a series of such changes may look so different that they are not intuitively recognisable as stemming from the same base hue.

Further, there are non-negotiable physical limits to what you can achieve by changing the lightness or darkness or chroma of a given hue. Different hues achieve highest saturation at different values: yellow, for example, is brightest at higher/lighter values, while blues and purples “max out” their chroma at lower/darker values. These are inherent properties, as inevitable as the straight path of a beam of light or the flow of water downhill.

Whether you are tracing a colour along an axis of the Munsell tree or whether you are moving a selection cursor to change these qualities in a paint program, you will always get the same result for the same given stepwise change in a hue, chroma or value. As the saying goes, you can’t make this stuff up. Colour simply is what it is, and it does what it does.

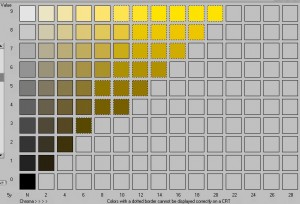

The following chart takes a single hue and alters chroma and value, and as we can see, a yellow cannot be both light and muted or bright and medium-dark; the brightest yellows have a clear lemon or saturated acid tinge and are all very high value, while at medium-dark and dark values the very same “yellow” hue is muted and resembles the colour we call “olive”. At a given point, then, a yellow can be light and bright OR relatively darker and muted, but it simply cannot be both. A bright dark yellow is physically impossible, and though the lower squares are still variations of yellow hue, our eye sees an intense, rich, muted colour which most people would *NOT* instinctively associate as related to the pure clarity and brightness of “yellow”.

In an accurate 12-tone system, then, colours are grouped in tones according to their relative position in these three parameters. This is why there are no truly “shared” or “overlapping” colours in the TCI colour palettes: a colour has a natural and singular place on the basis of hue, chroma and value, and simply cannot be placed in two tones at once. It is important to note that the tones were not developed by simple selection from the Munsell tree: Kalisz used her deep knowledge of the way colour flows in nature – from cool to warm to cool to warm, her profound mastery of subtractive colour mixing, and her understanding of how human beings perceive light in order to define and refine the parameters of each tonal grouping.

Now let’s look at the example of Light Spring and Soft Autumn. Both are warm neutral, both are the lightest members of their overall parent seasons, spring and autumn. Is there a season between them which we might call “Light Soft Autumn” or “Muted Light Spring”? Can we visually demonstrate such a thing?

Light Spring is defined as relatively light in value, fairly bright but slightly muted in chroma compared to the other springs and winters, and warm-neutral in hue. It has a quality of lightness and relative clarity compared with Soft Autumn, which is medium in chroma and rather more muted while still sharing the general hue temperature quality of warm-neutrality. These are the essential characteristics of these tones respectively.

Soft autumn has soft golds and very muted oranges rather than the light, clear yellows and brighter and lighter oranges of light spring (both of which are slightly lighter than True Springs), and while both have olives and greyed/desaturated warmed greens, Light Springs’ are relatively higher saturation and lighter overall than Soft Autumn’s darker versions. These selections in colour space are not random or arbitrary. They were very carefully defined so as to give harmonious relationships within the tone. As we have noted above, when we significantly mute and darken a Light colour or brighten a Soft colour beyond the tonal limits, then we have moved into another Tone, because colour moves in accordance with its own physical rules at all times as surely as one plus three equals four and not six. Notice that the only quality these tones really share is their warm neutral hue temperature. Once again: the two tones only have warm neutral in common (one dimension of colour) and the other two are opposed, with LSp being higher in chroma and SA being lower, LSp being lighter in value and SA being medium

What would happen, then, if we mixed a warm or warm neutral colour from one tone with a related or equivalent warm or warm-neutral colour from another? (In saying this, we are assuming that we are “on the same page” when choosing these hues, and that the colours involved in each case are of the same hue family – a green and a green, an orange and orange, or yellow and yellow, or in other words clearly related in terms of hue and temperature – things get more interesting when the substrate hues are substantially different.) The answer is that we would end up with an meld or average of the two colours which, depending on the proportions and final saturation reached, would fit into one of the existing warm or warm-neutral tones. I would qualify this further: home experimenting with subtractive colour mixing requires an intimate understanding of the constituent pigments, as in practice artist paint colour and powdered pigment is rarely “pure” in the sense of light frequencies absorbed and reflected, and may throw up unexpected results when combined. Few non-experts can adequately control for this; Kathryn Kalisz was a master of it.

Essentially, then, we are adding no new information when we combine these analogous versions of warm with warm or warm with warm neutral or warm neutral and warm neutral (assuming the same caveat above. Another way, perhaps simpler, is to imagine mixing two different swatches on a Munsell chart page together – the “new” swatch will inevitably be somewhere “on the same page”, as nothing new has been added to the mix.) Further explanation of this can be found in the TCI blog piece “Cool + Cool and Warm + Warm (January 28, 2011)” The result is a sum of the parts which will fit one or the other parent tones. Mixing warm and cool, on the other hand, gives us a neutral, and this was Kalisz’s key insight – the tones therefore move in natural order from warm to cool via warm-neutral and cool-neutral as the hue temperature shifts, and there are no areas of colour space unaccounted for in an accurate 12-tone system as the other properties of colour – value and chroma – place their own natural limits on what is possible.

There are therefore no colours that an accurate 12 -tone system would classify as “Light Soft Autumn”. There are lighter colours within soft autumn, of course, and the TCA Corporate palette explores these further for shirting purposes, but these are still more muted than anything that would properly be seen as light enough and bright enough to belong within the Light Spring tone. It is certainly possible to put colours from both together, but the result of this arbitrary grouping would not be as harmonious.

PRACTICAL PROBLEMS

There is no doubt that some colours and colour effects are more difficult to place due to texture, pattern mixtures, translucency, sheen, and so on, either because they somehow confound the viewer’s expectations of where this version of that colour might be found (that is, something about the texture or opacity or whatever is making it hard for the individual viewer to fit them into their internal mental “map” of how a given tone or tones might look) or because we are talking about structural colour with a shimmering, iridescent quality that may be harder to pin down (such as is seen in many feathers and insect wings).

It can be challenging to visualize these more dimensional colours amid the matte reference hues on your palette, and this is even harder if it happens to lie “off piste” for you and you aren’t sure where else it might belong.

This “classification/filing” issue is usually where the concern about “gaps in the record” has come from – the viewer sees something, can’t quite work out where it would fit, and so quite naturally wonders if the map is incomplete. But these colours are *always* accounted for, provided your experience of the tones is wide enough to let you see everything the palette is telling you.

In practice, several other things can make it harder to place a hue or an ensemble of them within the 12-tone system:

(1) The Tones approach each other very closely in places where they occupy adjoining areas of colour space, and while a colour may properly belong in one tone, it may take us very close indeed to the line where another begins.

(2) Style influences the way we “read” colour, especially if we have a belief that certain styles and colours go together.

(3) Fashion neutrals are low chroma, but the soft tones – Soft Autumn and especially Soft Summer – have low chroma even in respect of their accents, and there can be a tendency to assume that mid-value fashion neutrals belong to these Tones even when they serve other tones better.

(4) While everyone will have an optimal tone, many of us can and do fudge the margins just a bit in order to find something reasonable to wear, and these groupings of less tonally related pieces can confuse the lay eye, especially if grouped in advertorial digital or print magazine pieces or if lighting effects make subtle disharmony harder to see. Patterns can do this as well, grouping tones for effects which do not necessarily work to the harmonious ends we are aiming for here. Which leads us to the final confounder, so familiar to all of us who use the internet to shop:

(5) Photographs can shift reality. As anyone who has ever searched for a recommended lipstick shade in Google images knows, you make just about anything look like just about anything by the time you have lit it, shot it, shopped it, and put it on someone else’s monitor. Photographers lighten, brighten and otherwise enhance images with software all the time, and it is certainly possible to photograph or photo-enhance Light Spring and make it look like Soft Autumn, and vice versa (something that causes confusion and chagrin for online shoppers).

In a future article we will look at some simple practical illustrations of some of these issues.

5 replies to “Is There Any Colour Space Unaccounted For In A 12 Tone System?”

Thank you for this. I have a couple of questions: you say “Fashion neutrals are low chroma, but the soft tones – Soft Autumn and especially Soft Summer – have low chroma even in respect of their accents, and there can be a tendency to assume that mid-value fashion neutrals belong to these Tones even when they serve other tones better.”

How then can the fashion neutrals with low chroma belong in a high-chroma season? For example, as a Bright Winter, there are greys and grey-taupes in my palette. How can this be if all the colours in a palette are supposed to have the same properties?

Also, “A bright dark yellow is physically impossible.” Yes, but there are icy yellows on the Dark Winter palette too. These aren’t dark either?

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your enticle helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.